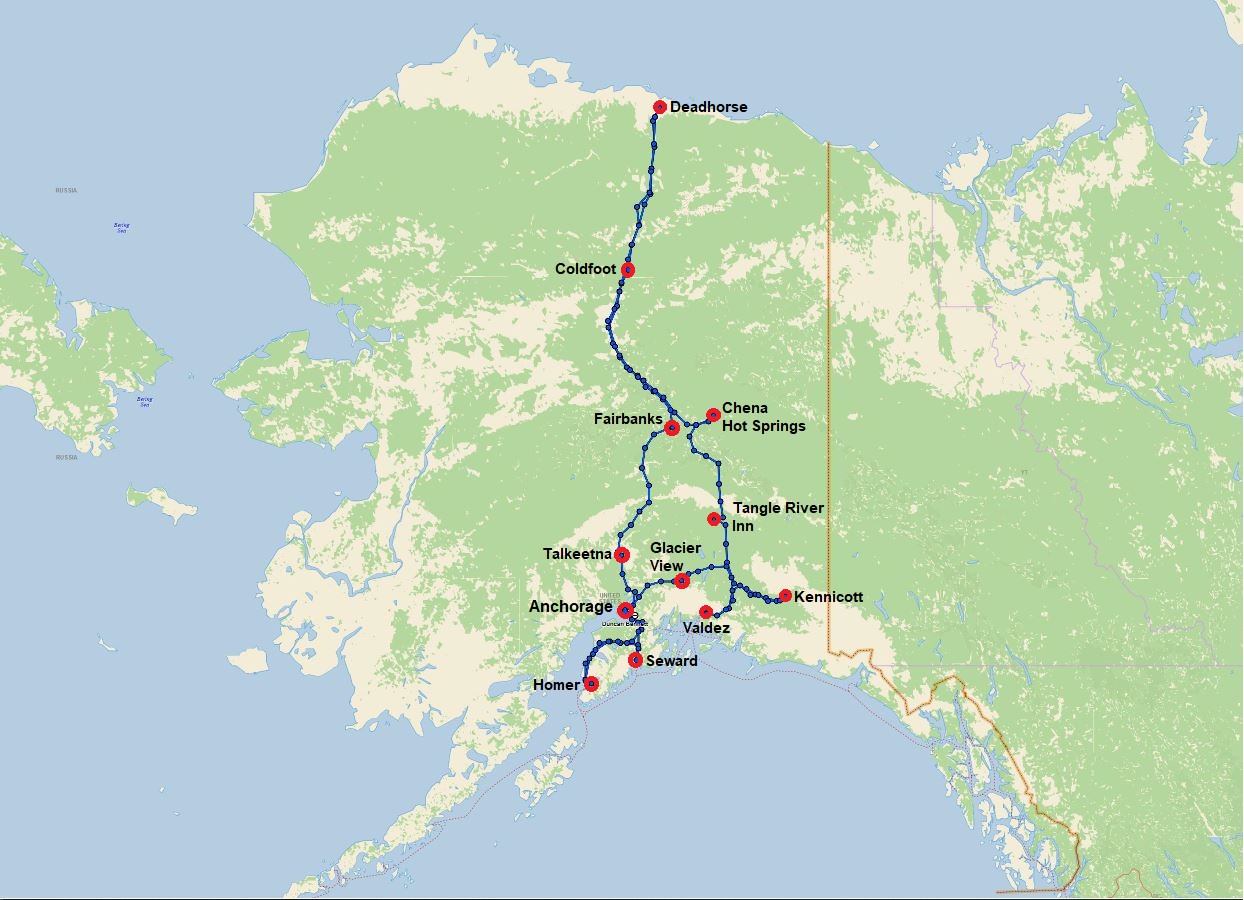

We left Part 1 Photo Bombe Alaska at the close of Day 5 in Talkeetna. Even though we seemed to have done a lot of riding, the northerly progress from Anchorage only added up to about 160km so to get to the top we were going to have to up the pace. Day 6 objective was Fairbanks, considered to be the most northerly civilisation in Alaska accessible by road, a journey of about 450km which would make a reasonable dent in the distance.

Road quality heading north past the sometimes nearly visible Denali ranges to the west was excellent, encouraging the leaders to indeed “up the pace”, until a member of Alaska’s constabulary decided that the pace was too up for his liking. It appears that state law allows for mass pull-overs with the officer’s opinion on whether the basic speeding law (driving too fast for the conditions irrespective of the posted speed limit) has been violated all that counts. We first realised we had a nest of dangerously reckless criminals in our midst when cresting a hill at a very safe speed and seeing flashing blue and red lights and a line of cars and motorcycles pulled to the side of the road. We went past by a hundred metres or so and pulled over, just so we could be clearly seen and provide a positive and timely example of how one should behave on public roads.

After battling mozzies for a while, the proceedings were completed with a slight increase in state revenue, Tim’s blood pressure, and his righteous indignation, so we headed up the road to the interesting Veteran’s Memorial Park. After consoling our victimised friends with deep and genuine expression of sympathy and a mozzie repelling candlelight vigil, we checked out the Park which has displays describing all the conflicts Alaskans have been involved in. The second world war is particularly interesting, and Alaska was the only place in the USA invaded; the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska were occupied by the Japanese in 1942 to protect their northern flank. Only a year later, US and Canadian forces expelled them to prevent any potential attack by the Japanese on the US north west coast.

With squadrons of mozzies beginning to make opening visors or mouths risky, we hit the road once more at a slighted less “upped pace”, travelling to Cantwell where the big Alaskan road loop is cut in half by the Denali Highway which was designed to provide tourist access from the eastern side of Alaska to the immensely popular Denali park. A push to the McKinley Creekside Café and we’d done enough to deserve an excellent burger lunch with chips that I always swore I’d never eat to keep the carbo-load down but always did. No fuel was available, so we continued up to Healy to undertake this essential service. The process for re-fuelling was becoming smooth by this point in the trip; Justin would pull into the servo, and try to get both sides of a single bowser to allow the other 14 bikes to conga line past in two columns and be filled. If all 15 bikes had to be filled in a single line, then it just took a bit longer. Not that there weren’t occasional snafus and indeed the only bike drop of the entire trip occurred at a servo, but the system was generally quite efficient.

Filled with food and fuel, the only thing remaining to do was to get to Fairbanks, although another stop was taken at the Roughwood Café in Nenana in case someone hadn’t loaded in 500% of their daily carbs requirement with more than two hours remaining before any carbo-sustaining dinner could be had. The accommodation in Fairbanks was at Pike’s Waterfront Lodge, designed for handling the enormous number of tourist groups coming through Fairbanks via train, plane, or bus. We did very well for ourselves and most of the group was sent out to the top-quality cabins next door to the lodge, probably because we were all so coated in splattered mozzies and other insects that they didn’t want us inside. The Lodge was a long way out of town; however this was later realised to be a good thing when some of the group went in to find dinner and discovered it mainly dead except for one craft brewery oasis. With Prudhoe Bay a dry area and lacking take-away facilities, Patrick O’Perth joined us for an Uber trip to the nearest Walgreens for a few liquid essentials before getting back to the lodge and calling it a day.

Day 7 was the start of the real Alaska, or at least the Alaska that most people including a lot of Alaskans haven’t seen. Not far out of town the roadworks started, giving us a refresher on riding gravel roads which would be most of the surface ridden for the following days. At Livengood, the last chance to loiter in civilisation is forsaken and the Dalton highway begins. The highway is named after James Dalton, a mining engineer who was a pioneer in oil exploration and was an expert in construction in Alaskan conditions – particularly on permafrost.

The first challenge was to make it to lunch at Yukon River, with the road a mixture of bitumen and dirt. The bitumen suffers from “frost heaves” when the water under the surface freezes and expands, creating speed bumps, drop-offs, whoops, and worst of all; potholes. The dry conditions made it pleasant riding, and the gravel sections were hard packed and easy. The Yukon River is big at the crossing – about 600m across, and that is before the huge Tanana River which flows past Fairbanks joins it to become a monster. A lunch of chilli which seemed to be lacking the obvious ingredient of chilli was enjoyed, before checking out the 800 mile long Prudhoe Bay to Valdez oil pipeline information at the crossing.

The rising temperature required some alteration in the number of layers worn under the jacket as we headed off north once more. The mainly hard-packed gravel continued with occasional patches of bitumen, making the speeds fairly high as we covered the 100km to the next important achievement – the Arctic Circle. As we were crossing the circle less than a week short of the summer solstice, our hopes of some cool dark nights to aid the sleeping environment were finally dashed. Some learned astronomy theory discussion was held amongst the “but it rises in the east and sets in the west” Australian contingent about where on earth the sun goes if it doesn’t set. The consensus was that we didn’t care, but needed better curtains.

Another 50km and we’d had experience of our first Dalton Highway roadworks at Gobbler’s Knob. As the highway is the heavy vehicle haulage route for the Prudhoe Bay oilfields, every effort is made to keep the surface as smooth as possible and keep the dust to a minimum. The roadworks crews use lots of water to get the compaction right, however this makes the road notoriously slippery when mixing in calcium chloride as a dust suppressant. Fortunately, we were all giggling about Gobbler’s Knob so didn’t get terribly focussed on the road condition, and all made it through without dramas. It was naturally broad daylight as we pulled into Coldfoot camp, famous as the major stop on the Ice Road Truckers television program. The accommodation was basic but good, and the truck stop mess hall and bar did their jobs admirably before getting to bed for a good day’s sleep in preparation for the final leg north.

Peter had volunteered to go out at second midday (12am) to see where the sun had gone, so Day 8 began with his explanation that it sort of just hovered, beaming a heavenly light on his 1200GS the entire time, which seemed about right and resolved the issue as far as the Australians were concerned. A hearty breakfast of oatmeal and we were packed and ready to roll on the most important day of the trip. For the first 40km the road was superb bitumen, then we started to get up into the Brooks Range which was the last barrier before the north slope and the tundra. A brief stop for morning refreshments, at which a seagull appeared once again proving that seagulls are literally everywhere, and we went over the top through a very scenic pass with the weather looking a bit ugly to the north.

Down we went onto the northern side, with trees suddenly a thing of the past. The road surface was generally excellent, even though it looked wet it was hard packed and allowed some good speed to be maintained by the group. The major problem was the cold which headed into the 40’s and ultimately the 30’s Fahrenheit as we went north in the overcast and slightly drizzly conditions. Stops were made to re-layer, which resulted in thick thermals top and bottom, riding t-shirt, long sleeved shirt, Gore-Tex gloves with two inner linings, double neck warmers, and a merino beanie under the extremely tight helmet. The Coloradans had come equipped with heated vests and gloves, and soon one could see the Australians mentally calculating their size just in case an opportunity presented itself to salvage.

The moisture got more serious as we reached the Sagavanirktok River (more conveniently just call the Sag River) and the inappropriately named Happy Valley camp for lunch. The cold was bitter, and wet mud was coating just about everything, making sandwich construction from scratch without ending up with an Earth condiment on the ham difficult. An experimental jog around the open spaces succeeded in making me tired without any appreciable increase in warmth, so stoically we all just had to stop thinking about hot soup, get back on the bikes, and keep going. The road continued in the hills beside the river and the surface generally remained good, until suddenly we were beside the river and into a 10km section of roadworks.

The roadworks had started on the right-hand side of the road, so the left-hand side was the preferred path as it appeared less slippery. Pace slowed and the tension was palpable, a wrong move would result in a hard fall and serious laundry issues. Riding on the wrong side was suitable until a truck came up behind us, fortunately it stayed on the right side and left us alone, unfortunately it put up a fine mist spray of chocolate coloured mud which completely coated us including the visors and other important equipment for seeing. A stop had to be made to clean visors, but Cindy suffered badly because her “pinlock” visor inside the main visor which is designed to act as double glazing and prevent fogging came loose. This resulted in fogging and having to open the visor to see, letting a literally arctic blast of air inside.

Soon the roadworks ended and the speed increased on an excellent gravel road, and then the animals appeared in the form of musk oxen, caribou, arctic hare, artic fox, and squirrels. A few stops were made for photos then we meandered along the long road through oil facility paraphernalia to reach the T-junction which signalled the end of independent riding.

Deadhorse is a bleak city of containers, industrial sheds, block buildings, dirt roads, oil and gas equipment, and lots of muddy space. Our first plan was to get fuel, then secondly get to the Prudhoe General Store which is the official end of the road for celebratory photos. Fortunately, the General Store is also a large and well stocked emporium with temperatures inside in the high 20’s Celsius, so it was not long before riders were re-warmed and ready to head to the accommodation. It was old-school camp living at the Deadhorse Camp; shared bathrooms are unusual in the modern world and no longer the norm in mining camps, but it made our experience a bit more gritty and we were comfortable enough in each other’s company by now to share facilities without staring or recoiling in horror. Once we were unpacked, it was off to dinner where another odd ritual was undertaken; getting food at the buffet required donning of gloves.

The slide into Day 9 completed without any intervening night, we had a tour planned to get to the coast and complete the northerly journey beyond reasonable doubt. To pass through the oil fields, we had to show our passports to the tour bus driver Cliff, who forcefully pushed home the fact that he was a security professional and not a real tour bus driver as we motored around Prudhoe Bay. Cliff was into detail and showed us how the workers live, normally a two-week on, two-week off roster. Cliff probably went into too much detail, by the time we had his room and phone number and directions to his room and his opposite number’s name who he shared the room with, in a hot bedding arrangement, we felt we were in deep enough. Gas flares were burning in the misty ride to the Beaufort Sea, and once past the drilling mud disposal facility we pulled up at the foggy coast. Cliff waited for a few minutes, probably to make sure that any polar bears had read his detailed instructions on not interfering with tourists, before we were released from the bus. With the promise of an official certificate signed by Cliff himself, various brave members decided to take the arctic swim.

With hypothermic members back on the bus, we headed away from the ultimate northern achievement, taking only photographs and leaving only footprints. And someone’s jocks. A few more stops at various places of interest involving Cliff’s lifestyle, and some good technical explanation about rigs and how they are moved, and we were back at Deadhorse Camp to complete the packing and prepare for the great southern journey.

The weather was a vast improvement from the previous day, with clear skies and dry crisp air that wasn’t too cold. Everything looked and felt better; the road, the scenery, the caribou, the fingers, and the toes. Pace was quick along the dry gravel roads, and even the nightmare roadworks section was a totally different proposition and gone was the slippery mud which had been replaced by a freshly graded surface that provided some reasonable grip.

Just after 2pm and we were back at the now appropriately named Happy Valley again for lunch, this time easily finding clean-ish surfaces to construct the sandwiches and even happily taking off layers and unzipping zips. The Brooks Range became visible to the south and east as we started off again, with numerous photo stops to take advantage of the glorious scenery that had been well hidden the previous day. Plans were made for Nic to deploy his drone to take footage as we climbed up into the pass, requiring some precision choreography for rider spacing which is always perfect until the film set is reached and everyone either bunches or spreads out or covers the other thespians with dust.

Stopping at the top of the pass, it was more photos, a bit of snow play for the Australians, and setting up for the next Nic film production. By this time everyone had realised that Margreth was the “A lister” in the film, so there was some jockeying for position trying to get as close in the line up as possible to her. Ride Leader Justin basically ruined it for everyone by riding alongside Margreth, but we didn’t have time to re-shoot so left it to Nic to “Kevin Spacey” him out of the final product.

Once down off the range, it was the slog through to Coldfoot with the last 30 miles mentally taking as long as the previous 100 because of the excellent bitumen road which actually made the riding a bit boring. The scenery maintained its fabulousness right up until the end, and the arrival back into Coldfoot wasn’t without some regret although we made it to the mess just before it closed and the bar had already run out of the decent craft beers so we were forced to buy US domestic. With the sun providing absolutely no assistance, it was left to checking the watch to see it was quite late and time for close of what had been a fantastic day.

Day 10 was quite a long day’s ride down to Chena Hot Springs, so we got ourselves organised as per normal quasi-religious routines and headed off at exactly 3 weeks after sunrise. First stop was at Gobbler’s Knob, where the roadworks had fortuitously moved on from, to get a view of the Prospect Camp in the valley below which holds the record for the coldest recorded temperature in the USA; -80°F or -62.2°C on 23rd January 1971. There is clearly a bit of shame that the North American record of -81°F is held by Canada at Snag in the Yukon, but bloody cold either way. Pushing on after a bit more giggling about Gobbler’s Knob, wide loads started to become a bit of an issue as it was good weather to move what looked like entire office blocks up to Prudhoe Bay, resulting in forced stops in wayside areas until the obstruction moved past.

At one stop south of the arctic circle, a well-dressed Japanese man and his lady friend approached us and asked where mobile reception might be available as they had a flat tyre on their hire car. Looking out across the endless taiga no mobile phone towers were immediately apparent, and although we were falling a bit behind, we decided that we would still likely make it to Chena Hot Springs in the daylight so pledged to help. To his eternal shame, our new Japanese friend had to admit that he had no idea how to change a tyre. In a few minutes the pit crew of Richard O’Roma, Bayne and I had the space saver tyre out, on, and the tools and punctured tyre packed away. Although unprepared for fixing vehicle problems, it was noted that the couple had enough food and water to survive more polar winters than the Franklin North-West Passage expedition, so we happily accepted a whole watermelon and hit the road once more. A bull moose on the edge of the road caused a momentary conniption, but it was worth it to see such an impressive beast as it bounded into the forest rather than into me. Unfortunately, the Japanese couple had started a trend, and about 20 miles shy of the Yukon River I noticed the front was getting wobbly, so pulled over in a wayside stop to discover a flat front tyre.

The cause was deduced to have been a rock I had inadvertently hit, but the solution in Bayne was a long time coming as he’d been trapped by yet another wide load. Getting as prepared as possible in the absence of any useful tools, we applied three fresh coats of Bushman’s and settled down to wait. Nearly an hour later Bayne arrived, and we got cracking on the first tubed tyre incident of the trip. First issue was finding the tools which had been provided by the bike hire company Motoquest. Successfully done, we (using the term we loosely by now) had the wheel off and discovered that Shinko tyres are bloody stiff which caused a lot of manly grunting and swearing to get the tube out and a new one in. All reassembled, Bayne applied his motorcycle tyre pump only to find that the valve wouldn’t seal, and the tyre stubbornly remained flat. Searching of the tool chest and spares for another 10 cent valve only increased the volume and frequency of swearing, so eventually we admitted defeat and unloaded the spare bike, a 1200GS. Fortunately it wasn’t far to Yukon River, unfortunately Nic’s latest cinema project of synchronised riding across the bridge had been wrapped up, and no celebrity level of tantrum would get him to re-shoot with me in it. A quick Caesar Salad lunch and we hit the road, not even bothering to stop at the Dalton Highway sign as we’d already done that, eventually catching up with the mob near Fairbanks after some roadworks that were way boggier and more slippery than anything we’d experienced on the Dalton Highway.

Once back into the vicinity of Fairbanks, the world was suddenly looking normal again and we turned east on the bitumen toward the resort at Chena Hot Springs. A final stop of fuel and some deserved take-away beverage procurement and we pulled into the resort just after 6pm, where the car park was discovered to have the highest density of mosquitoes and other biting insects of the trip so far. The feeling was nonetheless good and proud; we had ridden the Dalton Highway without serious incident and seen some incredible country, so with most of the dirt completed we were all well set for yet more spectacular scenery and wildlife in the remaining Alaskan south.

End of Part Two